- FORUM

- PROJECTS

- ABOUT US

- RESOURCES

- CONTACT US

- FORUM

- PROJECTS

- ABOUT US

- RESOURCES

- CONTACT US

The literary theory of Deconstruction holds that there is no fixed accessible truth, only chaos and multiple interpretations. The architecture spin-off simulates an appearance of chaos with dizzy, diverse perspectives. Vertigo and confusion are the desired responses.

Decon reflects a work out of whack. Its fragmented discontinuous forms represented the uncertainty of contemporary life after the downfall of the Soviet Union, Berlin Wall and 1987 stock market. Decon architects speak of the concept of “disturbed perfection,” symbolized by elements that seem randomly stacked, bent or tumbling.

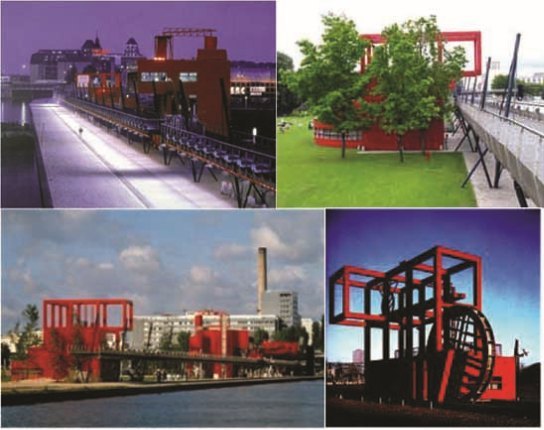

Bernhard Tschumi

The designs create non-sensual sculptures for an irrational world.

“Making things fit doesn’t make sense anymore,” the Swiss-born Tschumi said.

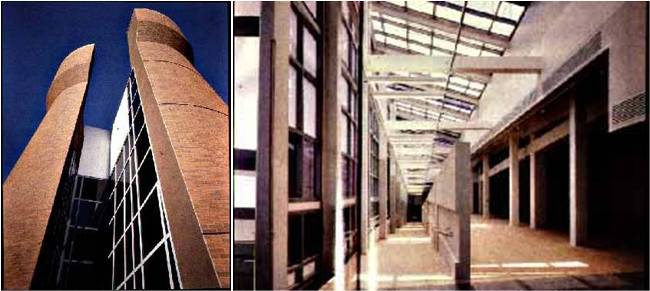

Decon follies (like Tschumi’s pavilions at La Villettein Paris) seek to promote dislocation, not provide cosy shelter. Decon is mostly paper architecture, in which many of designs published in magazines are clearly unbuildable: girders projecting at weird angles into air, beams that pierce space like pins in a voodoo doll, and columns without function seem to violate laws of gravity.

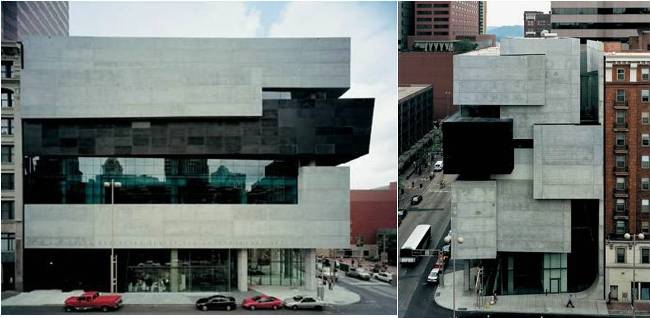

ZAHA HADID

At the age of eleven in her native Iraq, Zaha Hadid (b.1950) decided to be an architect. During her training in London, she became obsessed with the unfulfilled potential of Russian Constructivists, pioneers of Modernism in the 1910s and ’20s. “We can’t carry on as cake decorators and do these nostalgic buildings that have an intense degree of cuteness; we have to take on the task of investigating modernity,” Hadid told an interviewer.

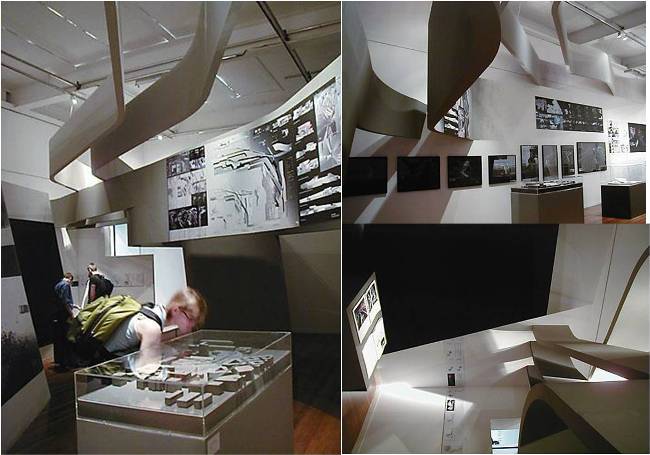

This whole idea of liberation from gravity is not because you are flying around in the air, but because you are freed from confining laws and conventions, and can make a fundamentally new kind of space,” Hadid explained in a 1992 interview. Her free forms and slicing axes convey a sense of thrust like the sharp fins of a 1950s Cadillac. Her diagonals and dislocations compromise what Hadid futuristically calls “planetary architecture.”

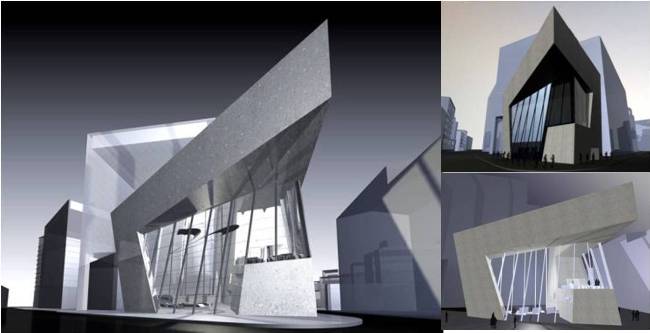

Peter Eisenman

Eventually he built several uninhabitable houses designated by Roman numerals to showcase his theories. House VI (1978) has a master bedroom with a floor split by a fissure where the marital bed would go. The void, for Eisenman, symbolizes the vacuity of contemporary culture. (Within ten years, the house had to be completely renovated by its owner.)

Eisenman is convinced that discomfort is vital to the experience of architecture. “Most people want architecture to remain casual,” he said. “My work is about making it uncasual.” Warping space so the viewer feels destabilized is how he awakens our senses to generate a fresh response. By undermining our comfort index, Eisenman jolts us out of boredom or indifference.

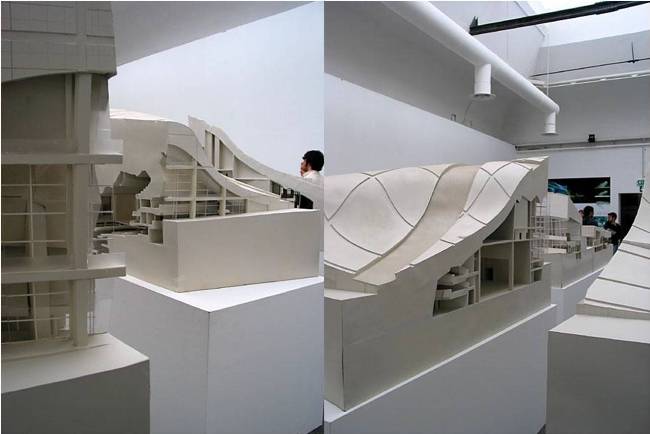

Intensely cerebral, Eisenman was an eminent provocateur in the 1980s, the high priest of Deconstructivism. Notorious for having two psychiatrists—one on the East Coast and one on the West—his neuroses and high anxiety are translated directly into his work. At the end of the 1990s, Eisenman entered a new phase. Enthusiastic about the capacity of computer-assisted design to generate expressionistic forms, he leapt on the bandwagon of sculptural form. To explain why he dumped Decon, Eisenman said, “There will always be four walls in architecture.” he hoped to create a “fluid architecture” with a “gelatinous quality” evoked by computer morphing.