- FORUM

- PROJECTS

- ABOUT US

- RESOURCES

- CONTACT US

- FORUM

- PROJECTS

- ABOUT US

- RESOURCES

- CONTACT US

An economic analysis of an urban infrastructure project would involve assessing the costs and benefits of the project in order to determine whether it is financially feasible and likely to provide a positive return on investment for the government, investors, and the community as a whole.

The costs of the project would include the initial construction costs, ongoing maintenance and operational expenses, and any financing costs associated with borrowing money to fund the project. These costs would need to be weighed against the expected benefits of the project, which might include increased economic activity, improved transportation options, and increased property values.

To conduct an economic analysis of an urban infrastructure project, it may be helpful to use one or more of the following tools:

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: A cost-benefit analysis involves identifying and quantifying the costs and benefits of a project in order to determine whether the benefits outweigh the costs. This approach can help to determine the financial viability of the project and identify any potential risks or uncertainties.

- Return on Investment (ROI) Analysis: An ROI analysis is a calculation that compares the expected financial return of an investment to the initial cost of the investment. This can help to determine whether the project is likely to provide a positive return on investment.

- Net Present Value (NPV) Analysis: A NPV analysis involves calculating the present value of the expected cash flows associated with the project, taking into account the time value of money. This can help to determine whether the project is likely to provide a positive net present value, which would suggest that the project is financially feasible.

- Sensitivity Analysis: A sensitivity analysis involves testing the impact of changes in key assumptions or variables on the financial viability of the project. This can help to identify any potential risks or uncertainties and assess the project’s resilience to changes in economic or market conditions.

Overall, an economic analysis of an urban infrastructure project is an important step in assessing the financial feasibility and potential impact of the project. It can help to identify any potential risks or uncertainties and ensure that the project provides a positive return on investment for all stakeholders involved.

An economic analysis is employed mainly by governments and international agencies to determine whether or not particular projects or policies will improve a community’s welfare and should therefore be supported.

The steps in preparing a standard economic evaluation are outlined below:

1. Definition Objectives: The starting point and in many ways the most crucial aspect for the evaluation of an investment proposal is the specification of the objectives of the proposal and their relation’to the overall objectives of the agency. No appraisal of the project can be meaningful unless the objectives are clearly defined.

2. Identification Options: It is necessary to identify the widest possible range of options at the earliest stage of the planning process. One alternative that should be considered is the possibility of the objective being met by the private sector. In developing various options the first option to be considered is the base case of “do nothing” i.e. retain the status quo. This is not to say the base case will not involve costs; in many cases doing nothing (for example continuing with a low maintenance programme) will result in cost penalties. One benefit of doing something may be the avoidance of these costs.

3. Identification of Costs and Benefits-The With-Without Principle: This is the basic principle of any type of project evaluation. In practice, it means that an attempt should be made to estimate the “the state of the world” as it will exist with the project in existence. This should be contrasted with the “state of the world” that would have existed in the absence of the project (the “do nothing” option).

This principle has two important implications:

First, economic evaluation must not simply be a comparison of before

project conditions with after project conditions because such comparison would attribute the contribution of all pre-existing trends and external factors to the project itself For example, reductions in on-going costs due to changed work practices should not be attributed to savings from an investment in new plant if the changes in work practices would have been introduced regardless of the investment decision.

Second, the analysis should include all impacts, both beneficial and otherwise, of the proposal being evaluated. In particular, not only should the intended effects or benefits which are the objectives of the project be included, but also the subsidiary or indirect effects.

Where valuation is possible, two key concepts need to be kept in mind.

a) The Opportunity Cost Principle: The use of resources (manpower, finance or land) in one particular area will preclude their use in any other. Hence the basis for valuing the resources used is the “opportunity cost” of committing resources; i.e. the value these resources would have in the most attractive alternative use.

The adoption of this principle reflects the fact that the economic evaluation of public sector projects should be conducted from the perspective of society as a whole and not from the point of view of a single agency.

b) Willingness-to-pay Principle: In valuing the benefits of a project the aim is to place a monetary value on the various outputs of the project. Typically such outputs will include:

i) benefits for which a price is paid; and

ii) benefits for which no price is paid.

Where the services are bought and sold it is generally presumed that the price

paid is a reasonable proxy for the values of the service to the consumer.

Specific Issues

a) Avoidance of Double Counting or Overstating of Benefits

In enumerating the costs and benefits of a proposal, care should be taken to avoid double counting. For example, the construction of a dam may increase the value of the land which is to be irrigated as a result of the increased ability of the land to grow crops. The increased value of the land merely reflects the market’s capitalisation of the increased output stream. Inclusion of the net value of the increased output and the

increased land value would count the same benefit twice

b) Treatment of Inflation

Due to inflation, costs and benefits which occur later will be higher in cash terms than similar costs or benefits which occur earlier.

c) Use of Shadow Prices

A shadow or accounting price is the price that economists attribute to a good or factor on the argument that it is more appropriate for the purpose of economic calculation than its existing price, if any. In evaluating any project, the economist may effectively correct a number of market prices and also attribute prices to unpriced gains and losses that it is expected to generate.

d) Valuation of Specific Cost Items

i) Land and Pre-existing Buildings / Plant

While a project may use land, buildings or plant already owned by an agency for which no payment will be made, the opportunity costs of these assets should be included

ii) Labour

In assessing labour costs, the value of existing labour resources transferred to the project, as well as additional labour required, should be included

iii) Overheads

Labour related overheads such as supervision, transport costs, administrative costs, printing and stationery etc., are also included.

iv) Residual Values

At the end of the planning horizon or project life, some assets may still have some value. Such assets may not have reached the end of their economic life and may still be of use to the agency or may be resale able.

Costs to be Excluded from Analysis

A number of items which are included as costs in accounting reports or financial appraisals should not be included in an economic evaluation of an investment proposal.

a) Sunk Costs

In an evaluation, all costs must relate to future expenditures only. The price paid 10 years ago for a piece of land or a plant item is of no relevance; it is the opportunity cost in terms of today’s value (or price) which must be included. All past or sunk costs are irrelevant and should be excluded.

b) Depreciation

Depreciation is an accounting means of allocating the cost of a capital asset over the years of its estimated useful life. It does not directly reflect any opportunity cost of capital.

c) Interest

As future cash flows are discounted to present value terms in economic evaluations, the choice of the discount rate is based on various factors which include the rate of interest. The discounting process removes the need to include interest rate in the cash flows.

Register & Download PDF for Educational Purposes Only

Project Planning and Management Study notes for M. plan Sem-II

project planning and management.pdf

Register as member and login to download attachment [pdf] by right-click the pdf link and Select “Save link as” use for Educational Purposes Only

FD Planning Community Forum Discussion

- What different types of Projects can be taken up for Urban Development?

- Project Appraisal of city level projects

- Demand Forecasting methods for Project

- Location analysis for a project

- Role and Responsibilities of Govt. Organizations in project management

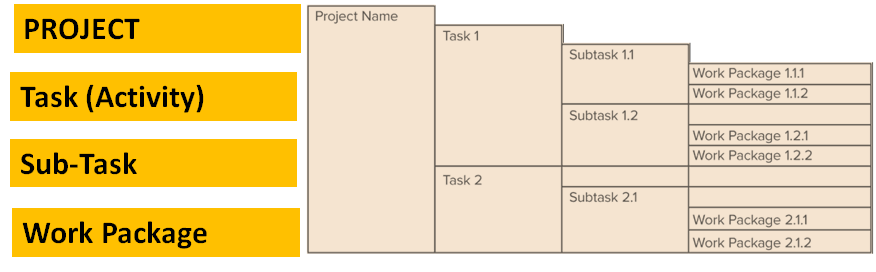

- Principles of activity planning

- Defining Activities of activity planning

- Sequencing Activities of Activity planning

- Estimating Activity Resources of Activity planning

- Develop Schedule of Activity planning

Disclaimer

Information on this site is purely for education purpose. The materials used and displayed on the Sites, including text, photographs, graphics, illustrations and artwork, video, music and sound, and names, logos, IS Codes, are copyrighted items of respective owners. Front Desk is not responsible and liable for information shared above.