Site planning is an important aspect of landscape design that involves analyzing and organizing outdoor spaces to create functional and aesthetically pleasing environments. It typically involves assessing the site’s characteristics, such as topography, soil, climate, and existing vegetation, and determining the best use of the space through strategic placement of features such as paths, plants, and outdoor structures. Effective site planning can enhance the usability and beauty of a site while also addressing issues such as drainage, accessibility, and sustainability.

Our primary work as landscape architect is to help fit human activities to the “want to be” of

the land.

Site planning in landscape design involves various elements, including:

1. Site analysis

The process of collecting and evaluating data about the site’s physical, ecological, and cultural features.

Now that we have selected the location, what is our next concern? At the same time that the program requirements are being studied and refined we must gain a thorough understanding of the site and its surroundings: not only the specific area contained within the property boundaries, but the total site, which includes the environs to the horizon and beyond.

Whatever we can see along the lines of approach is an extensional aspect of the site. Whatever we can see from the site (or will see in the probable future) is part of the site. Anything that can be heard, smelled, or felt from the property is part of the property. Any topographical feature, natural or built, that has any effect on the property or its use must be considered a planning factor

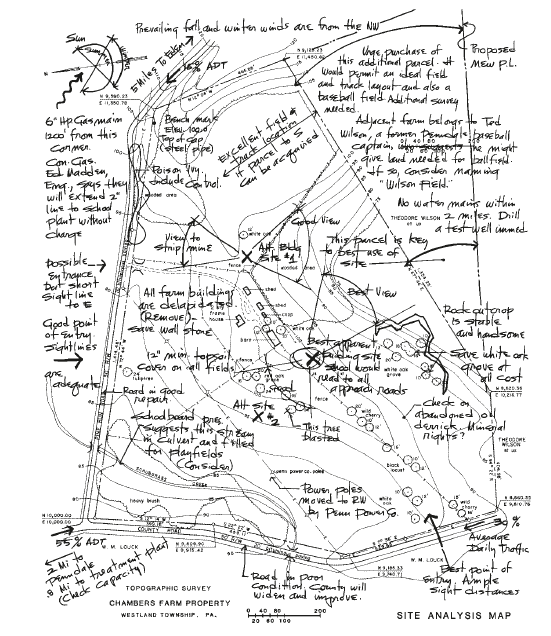

1.1 Site Analysis Map

One of the most effective means of developing a keen appreciation of the property and its nature is the preparation of a site analysis map. A print of the topographic survey furnished by the surveyor is taken into the field, and from actual site observation additional notes are jotted down upon it in the planner’s own symbols. These amplify the survey notations and describe all conditions on or related to the site that are pertinent in its planning. Such supplementary information might describe or note:

- Outstanding natural features such as springs, ponds, streams, rock ledges, specimen trees, contributing shrub masses, and established ground covers, all to be preserved insofar as possible

- Tentative outlines of proposed preservation, conservation, and development (PCD) areas

- Negative site features or hazards such as obsolete structures or deleterious materials to be removed, dead or diseased vegetation, noxious weed infestation, lack of topsoil, or evidence of landslides, subsidence, or flooding

- Directions and relative volumes of vehicular traffic flow on approach roads; points of connection to pedestrian routes, bikeways, and riding trails

- Logical points of site ingress or egress

- Potential building locations, use areas, or routes of movement

- Commanding observation points, overlook areas, and preferred viewing sectors

- Best views, to be featured, and objectionable views, to be screened, together with a brief note describing each

- Direction of prevailing winter winds and summer breezes

- Exposed, windswept areas and those protected by nearby topographical forms, groves, or structures

- Off-site attractions and nuisances

- An ecological and microclimatic analysis of the property and its environs

- Other factors of special significance in the project planning

In addition to such information observed in the field, further data gleaned from research may be noted on the site analysis map or included separately in the survey file. Such information might include:

- Abutting landownerships

- Names of utility companies whose lines are shown, company

- addresses, phone number, engineers

- Routes and data on projected utility lines

- Approach patterns of existing roads, drives, and walks

- Relative abutting roadway traffic counts

- Zoning restrictions, building codes, and building setback lines

- Mineral rights, depth of coal, mined-out areas

- Water quality and supply

- Core-boring logs and data

- Base map

2. Function:

Determining how the space will be used and designing it to meet those needs.

3. Circulation:

Planning the movement of people and vehicles through the site, including paths, roads, and entrances.

4. Grading and drainage:

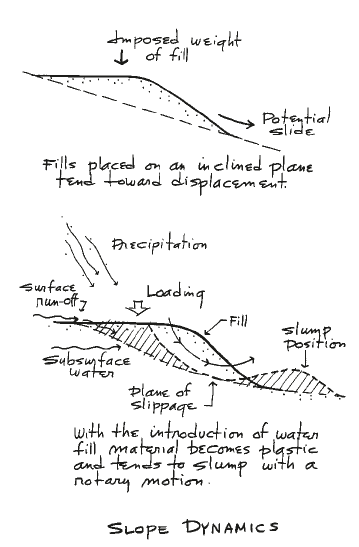

Altering the topography of the site to manage water flow and erosion. Contours are major plan factors. Contour planning (the alignment of plan elements parallel with the contours) is generally indicated.

The slope is a ramp. Ramps and steps are logical plan elements. The slope grade is perhaps too steep for wheeled traffic. Access is easiest along contours. This fact dictates a normal approach from the sides.

The pull of gravity is down the slope. Our design forms not only must have stability, they must express stability to be pleasing. An exception, of course, would be those structures in which a feeling of daring or conditioned exhilaration is desired.

The sloping site has a dynamic landscape quality. The site lends itself to dynamic plan forms. The dramatic quality of a slope is its apparent change in grade. Natural grade changes may be accentuated and dramatized through the use of terraces, overlook decks, and flying balconies.

A slope inherently emphasizes the meeting of earth and air. A level element imposed on a sloping plane often makes contact with the earth or rock at the inner side and is held free to the air at its outer extremity.

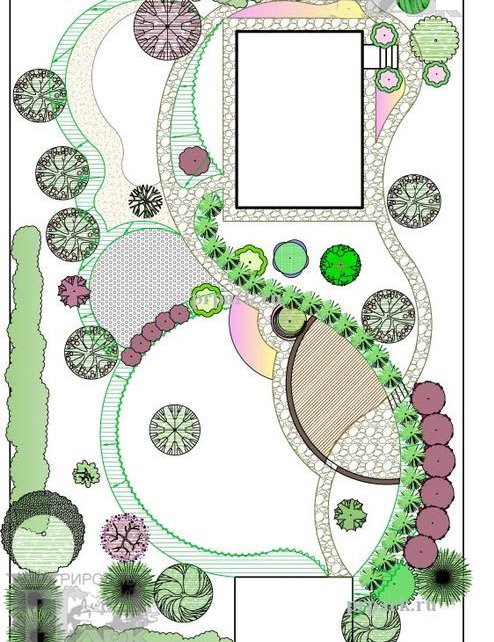

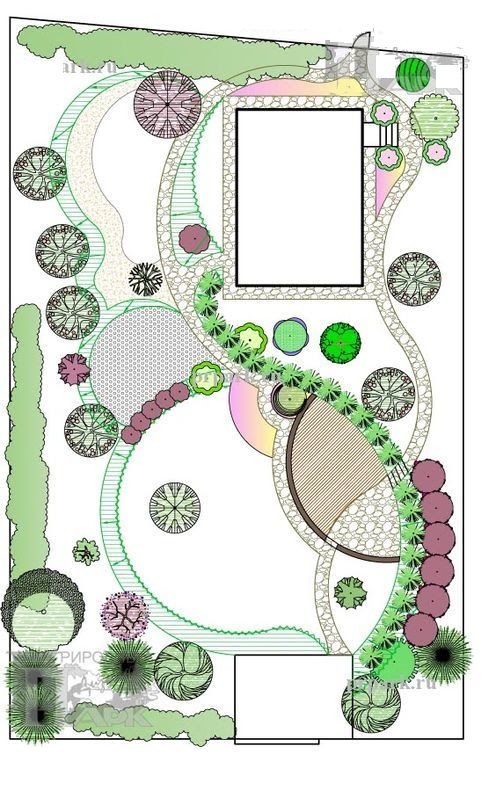

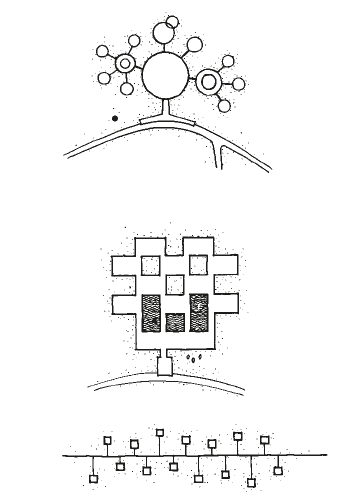

4.1 Level Site

A level site offers a minimum of plan restrictions. Of all site types, the level site best lends itself to the cell-bud, crystalline, or geometric plan pattern. A level site has relatively minor landscape interest. Plan interest depends upon the relationship of space to space, object to space, and object to

object.

crystalline, or geometric plan. taken from landscape architecture by A O Simonds

A flat site is essentially a broad-base plane. All elements set upon this plane are of strong visual importance, as is their relation one to the other. Each vertical element imposed must be considered not only in terms of its own form but also as a background against which other objects may be seen or across which shadow patterns may be cast. A flat site has no focal point. The most visually insistent element placed on this site will dominate the scene.

Lines of approach are not dictated by the topography. The possibility of approach from any side makes all elevations important. Lines of exterior and interior circulation are critical design elements since they control the visual unfolding of the plan.

Strategies for designing a landscape on a flat site:

- Create visual interest: Without the natural contours of a sloped site, it’s important to create visual interest and variety through the use of different plant materials, hardscaping features, and other design elements.

- Define spaces: Use plantings, hedges, or other features to create distinct areas within the site, such as a seating area, play area, or garden.

- Consider water management: On a flat site, it’s important to consider how water will drain and manage any potential drainage issues.

- Add hardscape features: A flat site can be an ideal canvas for adding hardscaping features such as patios, walkways, retaining walls, or other outdoor structures.

- Incorporate vertical elements: To add dimension and visual interest, consider incorporating vertical elements such as arbors, trellises, or raised garden beds.

- Use mass plantings: Planting large groups of the same type of plant can create a sense of continuity and flow, while also reducing maintenance requirements.

- Create shade: On a flat site, it’s important to create shade to protect people and plants from the sun. Consider adding trees, pergolas, or other shade structures.

5. Vegetation:

Selecting and placing plant materials to create a desired aesthetic and ecological effect.

6. Hardscape:

Designing and placing non-plant features such as walls, fences, patios, and other structures.

7. Sustainability:

Ensuring the long-term health and viability of the site through sustainable design practices and materials.

8. Safety and accessibility:

Addressing concerns related to pedestrian and vehicular safety and accessibility for people with disabilities.

9. Maintenance:

Planning for the ongoing care and maintenance of the site, including considerations for plant and hardscape maintenance and waste management.

From small-home grounds to campus, to park, to large industrial complex, site installation and maintenance costs can be reduced and performance improved by the standardization of all possible components, materials, and equipment. Use only the affordable best (quality and economy).

The number of construction materials and components and thus the replacement inventory of items that must be kept stocked are reduced to a workable minimum. This requires standardization of light globes, bench slats, anchor bolts, sign blanks, curb templates, paint colors, and everything else. Usually, a reduction in the quantity of items stocked can result in improved quality at significant savings. This is possible only if the maintenance operation is planned from the start as an efficient system or is converted to one.

10. Budget and scheduling:

Developing a budget and schedule for the implementation of the design, as well as any ongoing maintenance and improvements.

Disclaimer

Information on this site is purely for education purpose. The materials used and displayed on the Sites, including text, photographs, graphics, illustrations and artwork, video, music and sound, and names, logos, IS Codes, are copyrighted items of respective owners. Front Desk is not responsible and liable for information shared above.